One of the fundamental measurements of the Universe, called the Hubble constant, has been in doubt for years due to a wide range of independent distance indicators producing a persistent difference, called the Hubble Tension. However, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has seemingly confirmed that Hubble’s prior measurement of the expansion rate of the Universe was correct all along, leaving a new puzzle for scientists and astronomers to figure out.

A research team led by physicist Adam Riess of Johns Hopkins University used Hubble data and new observations from Webb to confirm that prior measurements were correct after years of debate. The conundrum that this new evidence presents, however, is that scientists have possibly been getting it all wrong.

“With measurement errors negated, what remains is the real and exciting possibility we have misunderstood the universe,” explained Riess. Riess is a Nobel Prize winner who co-discovered the fact that the universe’s expansion is accelerating, because of a phenomenon called “dark energy.”

Riess and his team used an initial Webb observation in 2023 to crosscheck and confirm that Hubble measurements of the expanding universe were indeed correct. This was not enough, however, to overcome the fact that different measurements provided contradictory values, called the Hubble Tension. Therefore, the team also conducted observations with Webb of other objects considered to be “cosmic milepost markers,” also known as Cepheid variable stars.

“We’ve now spanned the whole range of what Hubble observed, and we can rule out a measurement error as the cause of the Hubble Tension with very high confidence,” remarked Riess.

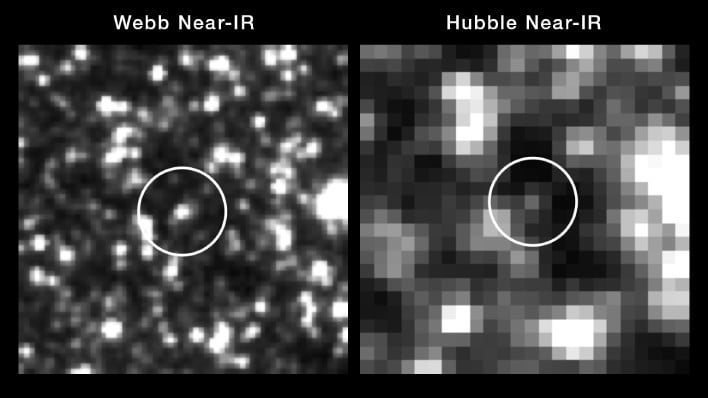

One star in particular that was observed was Cepheid variable star P42 in NGC 5468. Webb was able to reduce the clutter, allowing the Cepheid to stand out more clearly, and “eliminate any potential confusion.” Using samples Webb took of Cepheids, the team was able to confirm the accuracy of the previous Hubble observations that are fundamental to calculating the universe’s expansion rate and age.

Riess remarked, “Combining Webb and Hubble gives us the best of both worlds. We find that the Hubble measurements remain reliable as we climb farther along the cosmic distance ladder.”

There is still a puzzle left to figure out, however. While the distance ladder observed by Hubble and Webb has “firmly set an anchor point on one shoreline of a river,” the afterglow of the big bang observed by ESA’s Planck’s measurement from the beginning of the universe is firmly set on the other side. The question left to be answered is how the universe’s expansion was changing in the billions of years between the two endpoints.

Riess explains, “We need to find out if we are missing something on how to connect the beginning of the universe and the present day.”