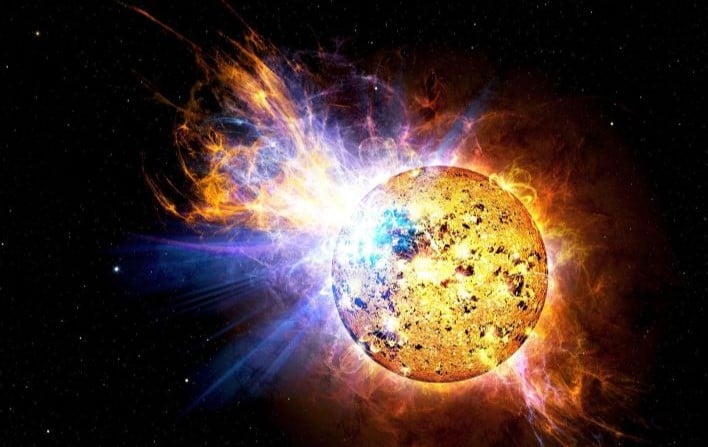

A new research has revealed that sun-like stars in our galaxy experience one violent “superflare” approximately once every hundred years—far more often that scientists previously thought. With that, many believe that the Sun in our solar system is overdue for such a superflare, especially since the last one was back in 664 B.C., according to evidences. If it happens again, the impact of that event on Earth’s technology infrastructure and compromised biosphere could potentially be catastrophic, but research mostly puts superflares as a great unknown for mankind.

According to a study published in Science.org, 56,000 sun-like stars were found to emit high-energy superflares once per century, which means the same thing can be expected for our Sun as well. If you thought solar flares were trouble—causing serious effects on Earth, such as communication systems and power infrastructure—the power of superflares might give you pause.

For context, the last BIG solar storm is arguably the Carrington Event in September 1859, of which a massive coronal mass ejection (CME) burst from the Sun’s upper atmosphere, traveled 17.6 hours to Earth, and knocked out global telegraph systems in the process, leaving Earth’s communication in silence. Auroral lightshows were seen all the way in the tropics, like in Honolulu and Cuba. According to NASA, CMEs usually take days to reach Earth, which shows the power of such a rare event.

However, the Carrington Event released roughly 1% of the energy of a regular superflare. Scientists had previously believed that superflares are, well, super rare, but based on Valeriy Vasilyev, a scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Germany, “Superflares on stars similar to our sun occur once per century. This is 40 to 50 times more frequent than previously thought.”

Vasilyev and his team collected data from NASA’s Kepler space telescope (ranging from 2009 to 2013), observing a total of 56,450 stars. The researches found 2,889 superflares on 2,537 of the total number of observed stars, equating to an average of one sun-like star producing one superflare every 100 or so years. The team also found that the frequency of solar flares and stellar flares is consistent between each other, therefore suggesting that the same mechanism generates flares on the sun-like stars, including our Sun.

The big question now is (besides when the next superflare will occur) is what will happen to Earth in such an event? There’s definitely a chance that our technological systems and fragile biosphere will be severely affected in the short term, not to mention how life on Earth could be changed after the fact. On the hand, some scientists have found that superflares tend to erupt closer to the poles of stars, which could mean that such a burst from our Sun could miss Earth entirely.