Sabrent’s lineup of internal and external SSDs is popular among enthusiasts. The primary reason is the company’s tendency to be among the first to market with products based on the latest controllers, while also delivering an excellent value proposition. The company has a long-standing relationship with Phison and adopts its controllers for many of their products. The company’s 2 GBps-class portable SSD – the Rocket nano V2 – is based on Phison’s U18 native controller, and has been available in the market for well over a year now.

This review takes a detailed look at the Rocket nano V2 External SSD, including an analysis of its performance consistency, power consumption, and thermal profile.

Rapid advancements in flash technology (including the development of 3D NAND and improvements in TLC reliability) have been accompanied by the appearance of faster host interfaces for external devices in the last decade. Together, they have contributed to bus-powered direct-attached storage devices growing in both storage capacity and speeds. The Type-C standard has also achieved widespread acceptance in the consumer market. Protocols such as USB 3.2 Gen 2×2 / USB4 and Thunderbolt riding on top of the Type-C connector have enabled the introduction of palm-sized flash-based storage devices capable of delivering 2 GBps+ speeds.

One of the primary challenges with high-speed storage devices is the thermal aspect. Bridge-based solutions with multiple protocol conversion chips tend to dissipate more power due to the additional components. High-performance portable SSDs in the past have had no option but to use them – first, with SATA bridges, and then with NVMe bridges. The introduction of native UFD controllers capable of hitting 10 Gbps and 20 Gbps from Phison and Silicon Motion has opened up yet another option in this category. The Crucial X6, equipped with the Phison U17, was reviewed in August 2021 and was one of the first retail products to surpass the SATA speeds barrier by hitting 800 MBps speeds without using a NVMe bridge. Around the same time, Silicon Motion’s SM2320 powered the Kingston XS2000 to 2 GBps speeds without a bridge in the middle.

Products based on Silicon Motion’s SM2320 have gained a lot of consumer mindshare because they have typically been able to hit the interface speed limits for sequential accesses in both the 10 Gbps and 20 Gbps categories. Phison’s U17 and U18 were introduced with slightly lower peak performance numbers, and despite vendors like Crucial picking them up for the X6, the products didn’t make any waves. The best implementation of Phison’s U17, in our opinion, was seen in the OWC Envoy Pro Mini. The introduction of faster flash has since allowed portable SSDs (PSSDs) based on the Phison’s native UFD controllers to hit higher speeds. As a result, we have seen an uptick in their adoption. Products such as the PNY EliteX-PRO, Sabrent Rocket Nano v2, and the Corsair EX100U are based on the Phison U18 controller. The EliteX-PRO’s performance was nothing to write home about. We reached out to Sabrent for a sample of the Rocket nano V2 to determine if it could be the ‘OWC Envoy Pro Mini equivalent’ for the U18 controller.

The PNY EliteX-PRO, Corsair EX100U, and the Sabrent Rocket nano V2 all use the same hardware platform – Phison’s U18 controller with 128L 3D TLC NAND from SK hynix. However, the firmware configuration, thermal solution, and case design are significantly different.

The Rocket nano V2 is small at approx. 72mm x 32mm x 14mm, but has a solid feel to it, thanks to its aluminum construction and 50g weight. The drive has a silicone cover that lends it protection against dents and scratches on the metal segment while also providing for a limited amount of ruggedness.

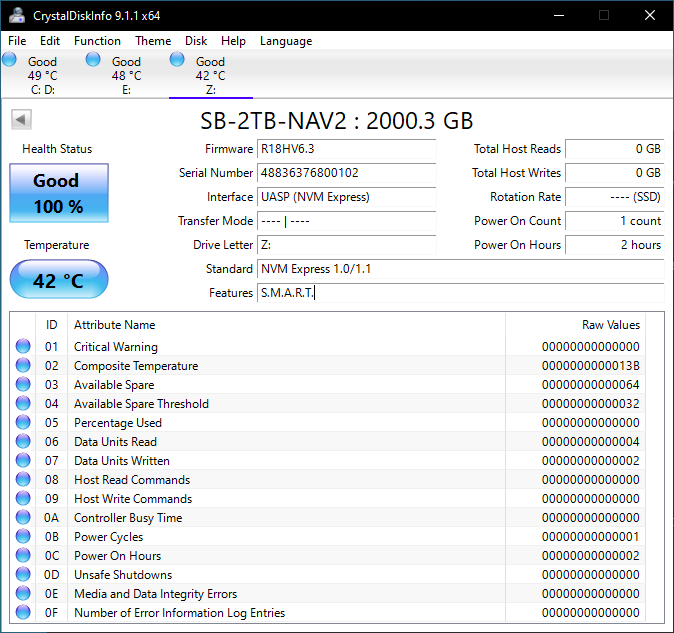

The Rocket nano V2 support S.M.A.R.T passthrough, as shown in the CrystalDiskInfo screenshots below. Despite TRIM not being noted in the features list, we found a NTFS volume on the PSSD successfully processing TRIM commands from Windows. All S.M.A.R.T features such as temperature read outs worked well.

| S.M.A.R.T Passthrough – CrystalDiskInfo | |

|

|

The table below presents a comparative view of the specifications of the different portable SSDs presented in this review.

| Comparative Direct-Attached Storage Devices Configuration | ||

| Aspect | ||

| Downstream Port | Native Flash | Native Flash |

| Upstream Port | USB 3.2 Gen 2×2 Type-C | USB 3.2 Gen 2×2 Type-C (Female) |

| Bridge Chip | Phison U18 | Silicon Motion SM2320 |

| Power | Bus Powered | Bus Powered |

| Use Case | Compact and rugged 2GBps-class portable SSD in a pocketable form-factor | 2GBps-class, IP66-rated, rugged palm-sized high-performance portable SSD with hardware encryption and a Type-C interface |

| Physical Dimensions | 72.4 mm x 32.5 mm x 14.5 mm | 86.2 mm x 54.4 mm x 13.2 mm |

| Weight | 50 grams (without cable) | 80 grams |

| Cable | 30 cm USB 3.2 Gen 2×2 Type-C to Type-C 30 cm USB 3.2 Gen 2 Type-C to Type-A |

30 cm USB 3.2 Gen 2 Type-C to Type-C Attached Type-C female to Type-A male adapter (resultant Type-C to Type-A cable length : 31.8 cm) |

| S.M.A.R.T Passthrough | Yes | Yes |

| UASP Support | Yes | Yes |

| TRIM Passthrough | Yes | Yes |

| Hardware Encryption | Not Available | Yes |

| Evaluated Storage | SK hynix 128L 3D TLC | YMTC 128L 3D TLC (packaged by Longsys) |

| Price | USD 182 | $240 |

| Review Link | Sabrent Rocket nano V2 External SSD 2TB Review | Lexar ARMOR 700 2TB Review |

Prior to looking at the benchmark numbers, power consumption, and thermal solution effectiveness, a description of the testbed setup and evaluation methodology is provided.

Testbed Setup and Evaluation Methodology

Direct-attached storage devices (including thumb drives) are evaluated using the Quartz Canyon NUC (essentially, the Xeon / ECC version of the Ghost Canyon NUC) configured with 2x 16GB DDR4-2667 ECC SODIMMs and a PCIe 3.0 x4 NVMe SSD – the IM2P33E8 1TB from ADATA.

The most attractive aspect of the Quartz Canyon NUC is the presence of two PCIe slots (electrically, x16 and x4) for add-in cards. In the absence of a discrete GPU – for which there is no need in a DAS testbed – both slots are available. In fact, we also added a spare SanDisk Extreme PRO M.2 NVMe SSD to the CPU direct-attached M.2 22110 slot in the baseboard in order to avoid DMI bottlenecks when evaluating Thunderbolt 3 devices. This still allows for two add-in cards operating at x8 (x16 electrical) and x4 (x4 electrical). Since the Quartz Canyon NUC doesn’t have a native USB 3.2 Gen 2×2 port, Silverstone’s SST-ECU06 add-in card was installed in the x4 slot. All non-Thunderbolt devices are tested using the Type-C port enabled by the SST-ECU06.

The specifications of the testbed are summarized in the table below:

| The 2021 AnandTech DAS Testbed Configuration | |

| System | Intel Quartz Canyon NUC9vXQNX |

| CPU | Intel Xeon E-2286M |

| Memory | ADATA Industrial AD4B3200716G22 32 GB (2x 16GB) DDR4-3200 ECC @ 22-22-22-52 |

| OS Drive | ADATA Industrial IM2P33E8 NVMe 1TB |

| Secondary Drive | SanDisk Extreme PRO M.2 NVMe 3D SSD 1TB |

| Add-on Card | SilverStone Tek SST-ECU06 USB 3.2 Gen 2×2 Type-C Host |

| OS | Windows 10 Enterprise x64 (21H1) |

| Thanks to ADATA, Intel, and SilverStone Tek for the build components | |

The testbed hardware is only one segment of the evaluation. Over the last few years, the typical direct-attached storage workloads for memory cards have also evolved. High bit-rate 4K videos at 60fps have become quite common, and 8K videos are starting to make an appearance. Game install sizes have also grown steadily even in portable game consoles, thanks to high resolution textures and artwork. Keeping these in mind, our evaluation scheme for portable SSDs and UFDs involves multiple workloads which are described in detail in the corresponding sections.

- Synthetic workloads using CrystalDiskMark and ATTO

- Real-world access traces using PCMark 10’s storage benchmark

- Custom robocopy workloads reflective of typical DAS usage

- Sequential write stress test

In the next couple of sections, we have an overview of the performance of the Sabrent Rocket nano V2 in these benchmarks. Prior to providing concluding remarks, we have some observations on the drives’ power consumption numbers and thermal solution also.

Benchmarks such as ATTO and CrystalDiskMark help provide a quick look at the performance of the direct-attached storage device. The results translate to the instantaneous performance numbers that consumers can expect for specific workloads, but do not account for changes in behavior when the unit is subject to long-term conditioning and/or thermal throttling. Yet another use of these synthetic benchmarks is the ability to gather information regarding support for specific storage device features that affect performance.

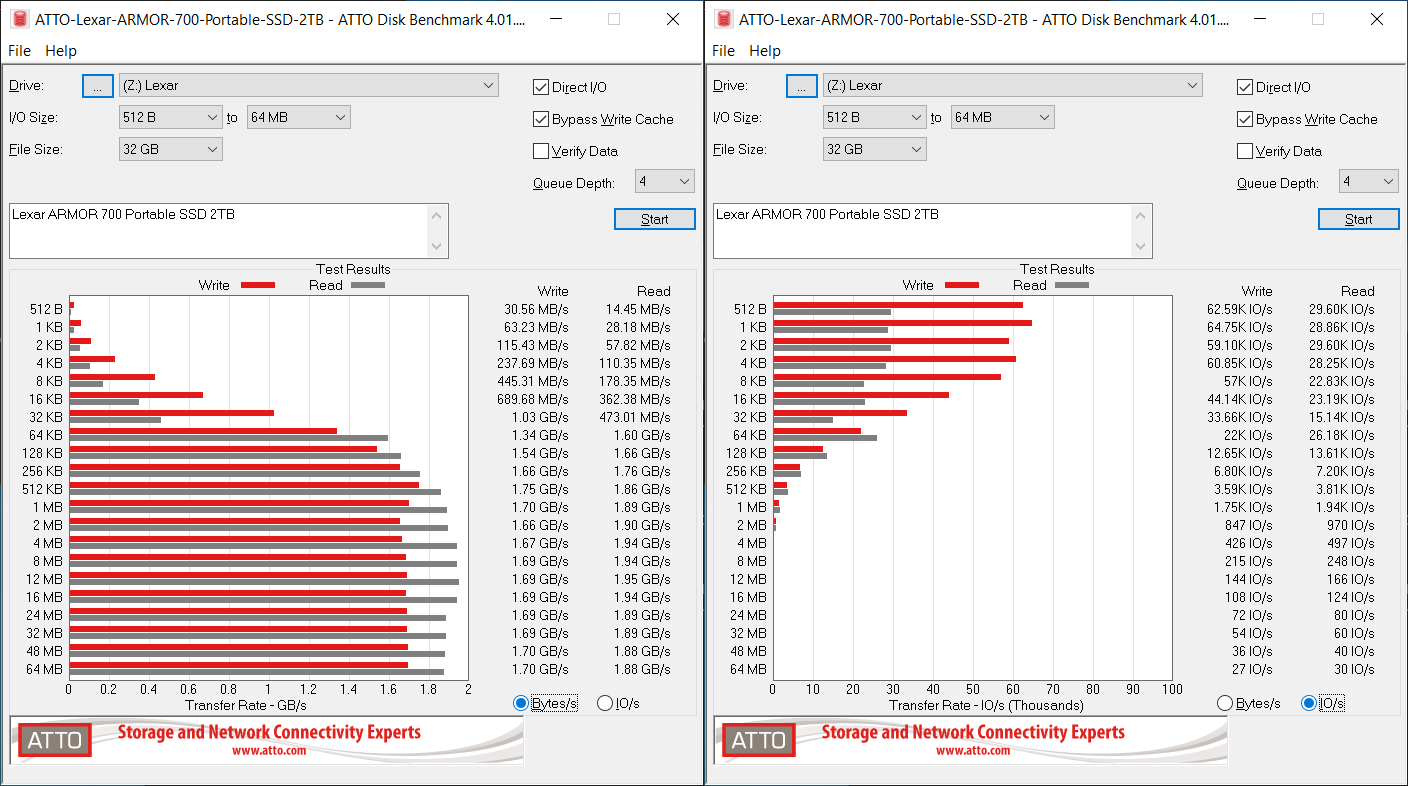

Sabrent claims transfer speeds of 1500 MBps, and that is backed up by the ATTO benchmarks provided below. ATTO benchmarking is restricted to a single configuration in terms of queue depth, and is only representative of a small sub-set of real-world workloads. It does allow the visualization of change in transfer rates as the I/O size changes, with optimal performance being reached around 512 KB for a queue depth of 4.

| ATTO Benchmarks | |

| TOP: | BOTTOM: |

|

|

|

|

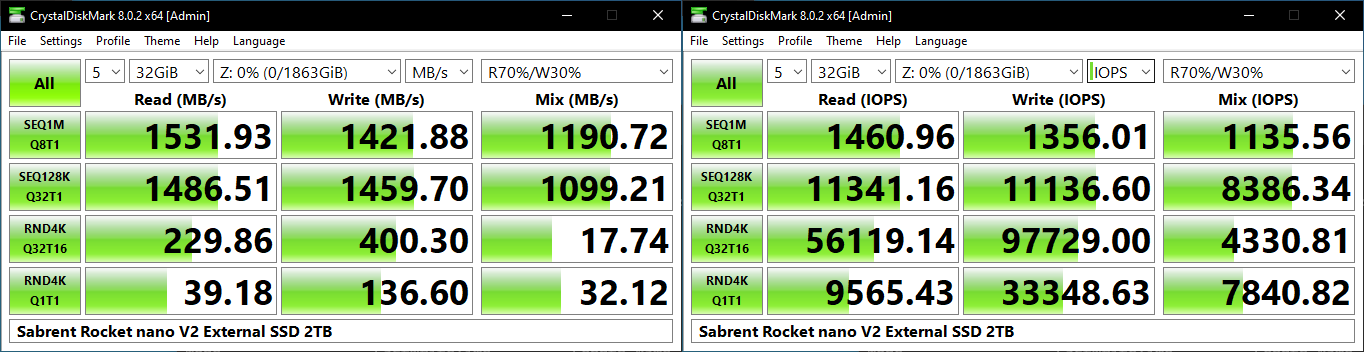

CrystalDiskMark uses four different access traces for reads and writes over a configurable region size. Two of the traces are sequential accesses, while two are 4K random accesses. Internally, CrystalDiskMark uses the Microsoft DiskSpd storage testing tool. The ‘Seq128K Q32T1’ sequential traces use 128K block size with a queue depth of 32 from a single thread, while the ‘4K Q32T16’ one does random 4K accesses with the same queue configuration, but from multiple threads. The ‘Seq1M’ traces use a 1MiB block size. The plain ‘Rnd4K’ one uses only a single queue and single thread . Comparing the ‘4K Q32T16’ and ‘4K Q1T1’ numbers can quickly tell us whether the storage device supports NCQ (native command queuing) / UASP (USB-attached SCSI protocol). If the numbers for the two access traces are in the same ballpark, NCQ / UASP is not supported. This assumes that the host port / drivers on the PC support UASP.

| CrystalDiskMark Benchmarks | |

| TOP: | BOTTOM: |

|

|

|

|

The performance of the Rocket nano V2 in these two synthetic benchmarks closely mirrors that of the PNY EliteX-PRO. Give the similarity in the platforms, it is not surprising. Overall, for small data spans such as 32 GB, the SM2320-based PSSDs surpass the performance of the U18-based ones.

Our testing methodology for storage bridges / direct-attached storage units takes into consideration the usual use-case for such devices. A description of the AnandTech DAS Suite and its components is available here.

It can be seen that there is no significant gulf in the numbers between the different units for most workloads. For all practical purposes, the average user will notice no difference between them in the course of normal usage, but power users may find the SM2320-based PSSDs and bridge-based PSSDs better for casual transfers. Power users may want to dig deeper to understand the limits of each device. To address this concern, we also instrumented our evaluation scheme for determining performance consistency.

Performance Consistency

Aspects influencing the performance consistency include SLC caching and thermal throttling / firmware caps on access rates to avoid overheating. This is important for power users, as the last thing that they want to see when copying over 100s of GB of data is the transfer rate going down to USB 2.0 speeds.

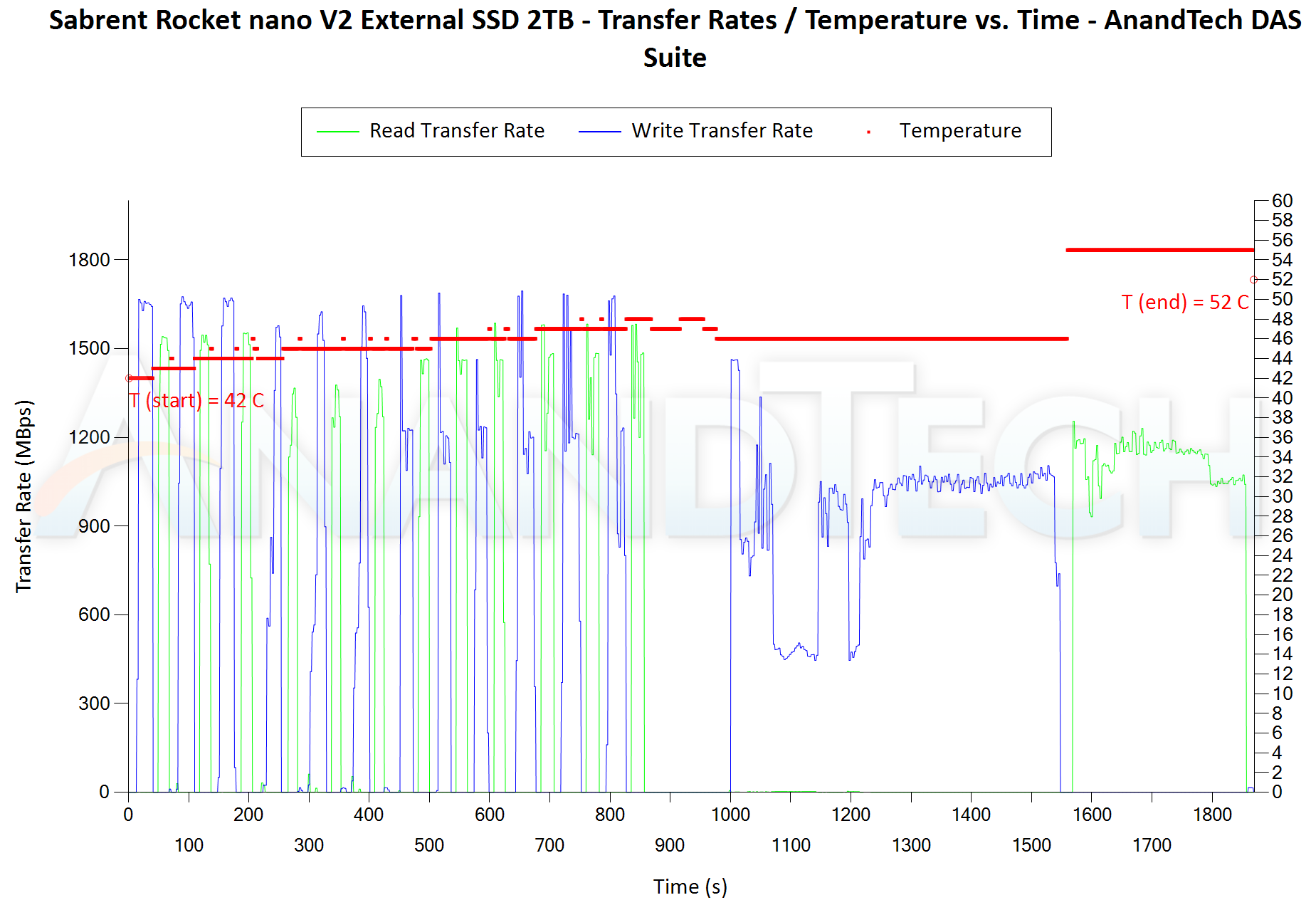

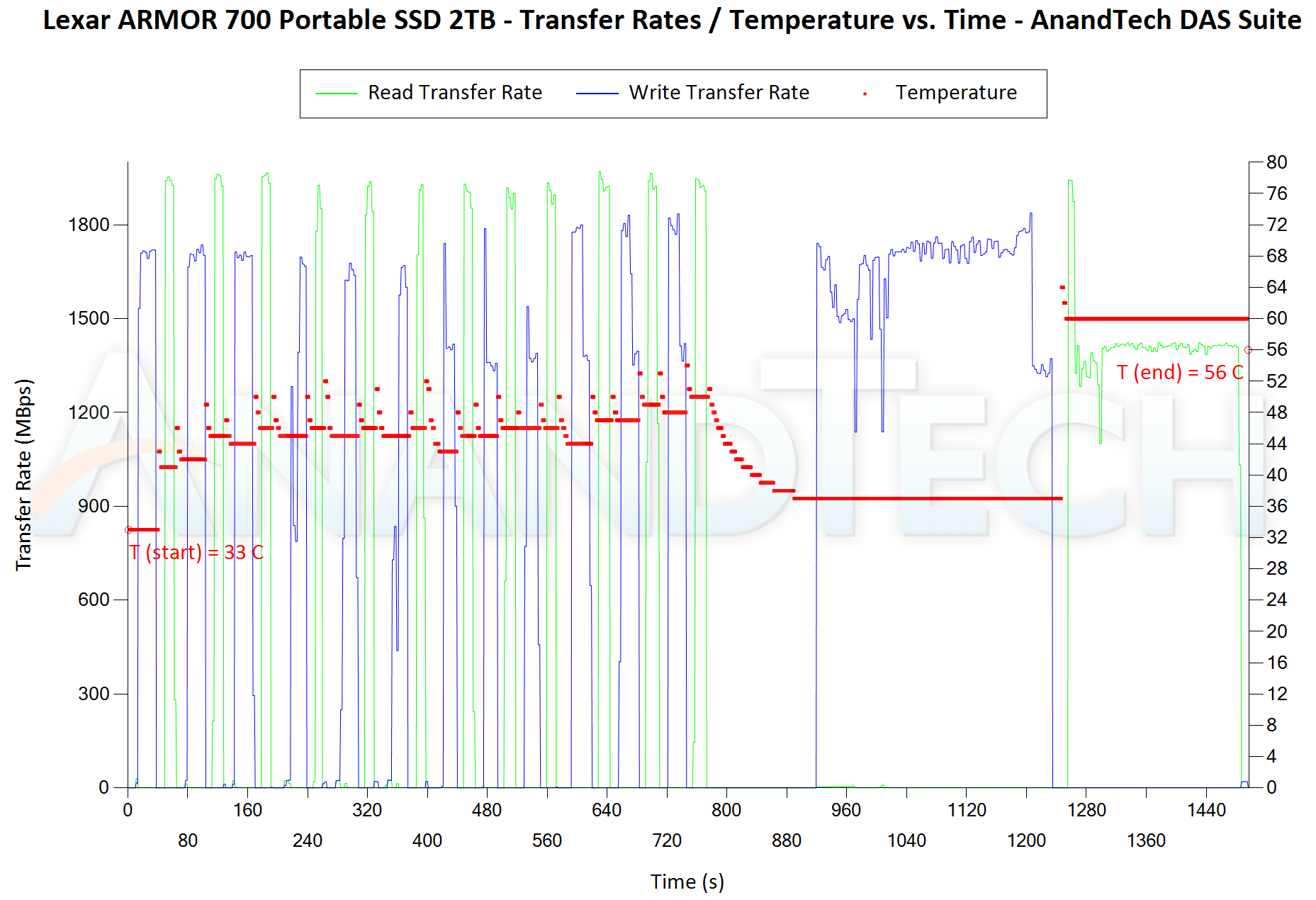

In addition to tracking the instantaneous read and write speeds of the DAS when processing the AnandTech DAS Suite, the temperature of the drive was also recorded. In earlier reviews, we used to track the temperature all through. However, we have observed that SMART read-outs for the temperature in NVMe SSDs using USB 3.2 Gen 2 bridge chips end up negatively affecting the actual transfer rates. To avoid this problem, we have restricted ourselves to recording the temperature only during the idling intervals. The graphs below present the recorded data.

| AnandTech DAS Suite – Performance Consistency | |

| TOP: | BOTTOM: |

|

|

|

|

The first three sets of writes and reads correspond to the AV suite. A small gap (for the transfer of the video suite from the internal SSD to the RAM drive) is followed by three sets for the Home suite. Another small RAM-drive transfer gap is followed by three sets for the Blu-ray folder. This is followed up with the large-sized ISO files set. Finally, we have the single disk-to-disk transfer set. These workloads show the first divergence point of the Sabrent Rocket nano V2 from the PNY EliteX-PRO. Thanks to its aluminum body and internal thermal solution, the drive is able to keep its cool, hitting a maximum of just 55C (compared to the 76C f the PNY EliteX-PRO). As a result, we do not have the thermal throttling during the disk-to-disk transfer set, and the full workload completes much faster than it did on the PNY EliteX-PRO.

There are a number of storage benchmarks that can subject a device to artificial access traces by varying the mix of reads and writes, the access block sizes, and the queue depth / number of outstanding data requests. We saw results from two popular ones – ATTO, and CrystalDiskMark – in a previous section. More serious benchmarks, however, actually replicate access traces from real-world workloads to determine the suitability of a particular device for a particular workload. Real-world access traces may be used for simulating the behavior of computing activities that are limited by storage performance. Examples include booting an operating system or loading a particular game from the disk.

PCMark 10’s storage bench (introduced in v2.1.2153) addresses this aspect with a variety of traces, as explained here.

Component Scores

The various component scores are graphed in the galler below.

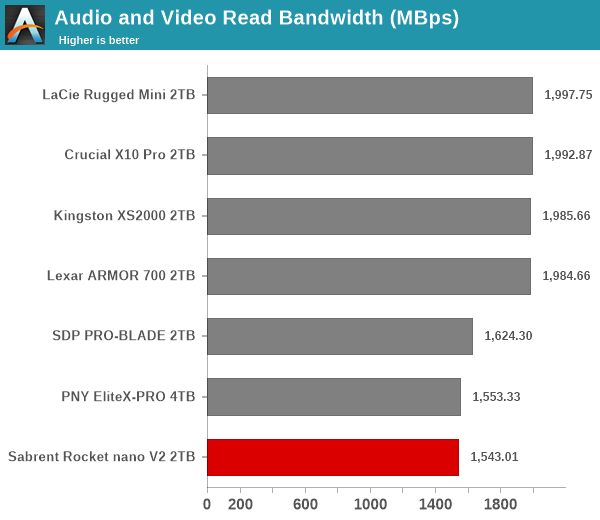

The Rocket nano V2 is consistently in the bottom half of the pack, but the delta is not extreme.

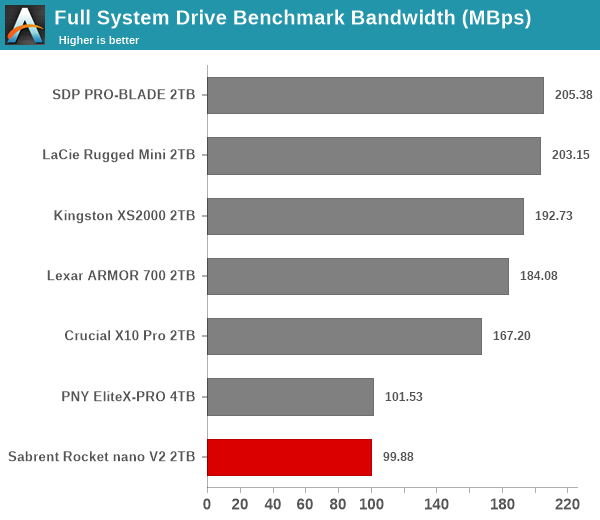

Overall Scores

PCMark 10 reports an overall score based on the observed bandwidth and access times for the full workload set. The score, bandwidth, and average access latency for each of the drives are presented below.

The PCMark 10 Storage Bench workloads are relatively light, and not enough to bring out the delta between the PNY EliteX-PRO and the Rocket nano V2. They both end up with similar scores, while the bridge-based solution is on top and the SM2320-based PSSDs make up the middle of the pack.

The performance of the storage bridges / drives in various real-world access traces as well as synthetic workloads was brought out in the preceding sections. We also looked at the performance consistency for these cases. Power users may also be interested in performance consistency under worst-case conditions, as well as drive power consumption. The latter is also important when used with battery powered devices such as notebooks and smartphones. Pricing is also an important aspect. We analyze each of these in detail below.

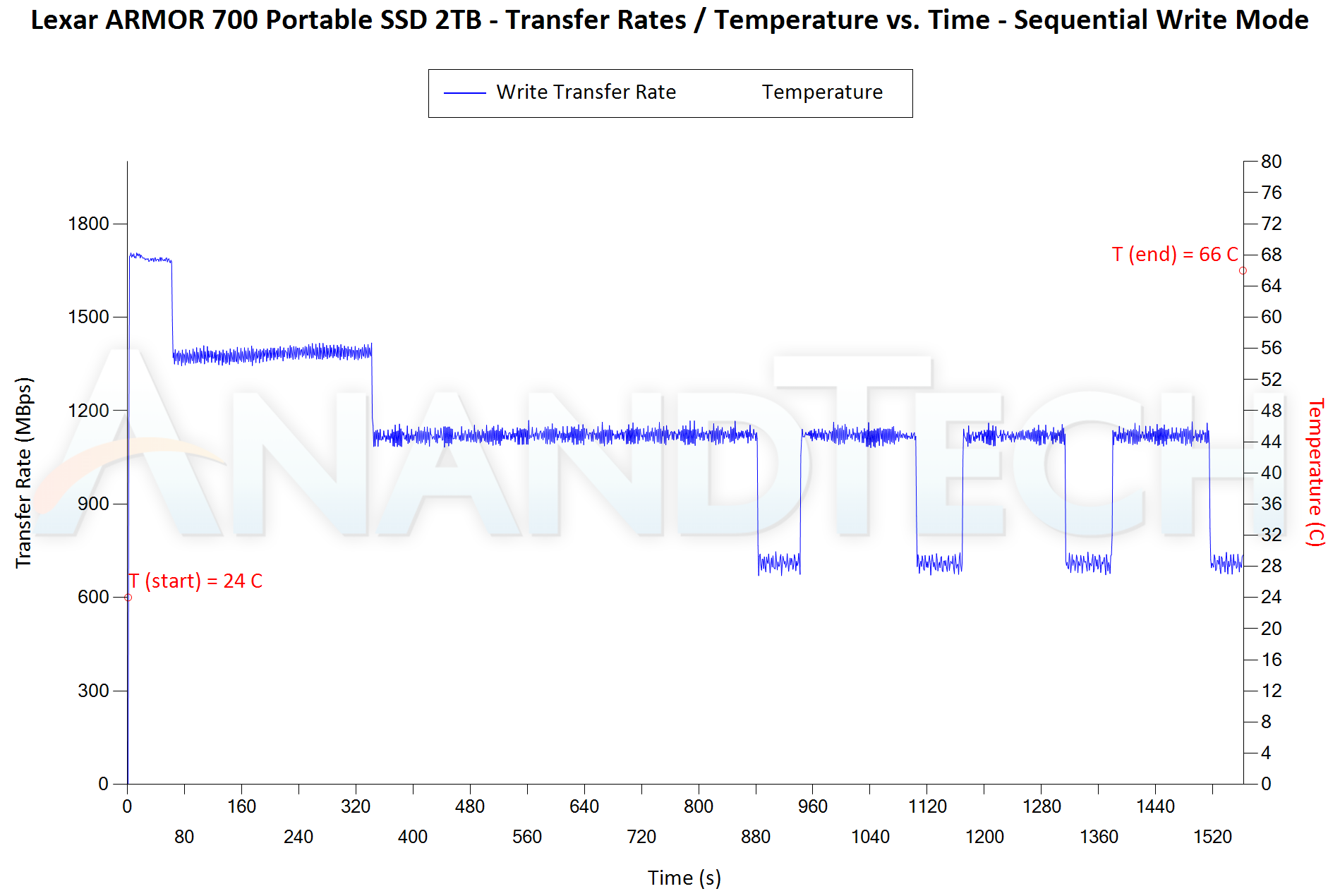

Worst-Case Performance Consistency

Flash-based storage devices tend to slow down in unpredictable ways when subject to a large number of small-sized random writes. Many benchmarks use that scheme to pre-condition devices prior to the actual testing in order to get a worst-case representative number. Fortunately, such workloads are uncommon for direct-attached storage devices, where workloads are largely sequential in nature. Use of SLC caching as well as firmware caps to prevent overheating may cause drop in write speeds when a flash-based DAS device is subject to sustained sequential writes.

Our Sequential Writes Performance Consistency Test configures the device as a raw physical disk (after deleting configured volumes). A fio workload is set up to write sequential data to the raw drive with a block size of 128K and iodepth of 32 to cover 90% of the drive capacity. The internal temperature is recorded at either end of the workload, while the instantaneous write data rate and cumulative total write data amount are recorded at 1-second intervals.

| Sequential Writes to 90% Capacity – Performance Consistency | |

| TOP: | BOTTOM: |

|

|

|

|

The Sabrent Rocket nano V2 shines here with excellent performance consistency – maintaining close to 800 MBps through 90% of the drive’s capacity. The temperature at the end was only 61C. The PNY EliteX-PRO with similar hardware presents a stark contrast – thermally throttling with temperatures ending up at 76C despite the write speeds falling to the 450 MBps range after less than 6 minutes of sustained traffic.

Some of the SM2320-based PSSDs such as the Crucial X10 Pro and the Lexar ARMOR 700 present better numbers in this test, but the Rocket nano V2 stands out in the Phison crowd and against other SM2320-based PSSDs such as the LaCie Rugged Mini.

Power Consumption

Bus-powered devices can configure themselves to operate within the power delivery constraints of the host port. While Thunderbolt ports are guaranteed to supply up to 15W for client devices, USB 2.0 ports are guaranteed to deliver only 2.5W (500mA @ 5V). In this context, it is interesting to have a fine-grained look at the power consumption profile of the various external drives. Using the ChargerLAB KM003C, the bus power consumption of the drives was tracked while processing the CrystalDiskMark workloads (separated by 5s intervals). The graphs below plot the instantaneous bus power consumption against time, while singling out the maximum and minimum power consumption numbers.

| CrystalDiskMark Workloads – Power Consumption | |

| TOP: | BOTTOM: |

|

|

|

|

Sabrent slips up a little on the power front – the drive idles at 0.76W (around 100 mW higher than most other PSSDs based on native controllers). The sleep mode also triggers only after 50+ minutes of traffic absence – this is contrast to other PSSDs where the sleep mode can be observed in the graphs above (triggered within 20 minutes of the end of traffic). This could be a minor issue when the drive is used with notebooks, but doesn’t matter for desktop usage.

Final Words

The Sabrent Rocket nano V2 2 TB version is priced at $182, which is around the same ballpark as other 2 TB PSSDs based on native controllers.

The value proposition of the Rocket nano V2 may appear weak if only the advertised transfer numbers and performance over small workloads / access spans is considered. There is scope for improvement in terms of power management and performance over short bursts. However, the drive truly shines with excellent performance consistency for sustained writes over long durations (common, for example, in video recording scenarios). The excellent thermal design ensures that the internals do not get too hot, and the silicone cover ensures handling safety. Overall, it is a promising choice for many use-cases, and opting for it over drives like the Crucial X10 Pro and Lexar ARMOR 700 depends on the end-user’s requirements and form-factor preference.